- Home

- M. G. Leonard

Danger at Dead Man's Pass Page 6

Danger at Dead Man's Pass Read online

Page 6

‘Maybe Arnie’s decided to be nicer today,’ Hal said to Ozan.

‘He said, Good morning, ass with ears,’ Ozan replied. ‘It means idiot.’

‘He’s not a nice brother,’ Hal observed, feeling sorry for the miserable-looking Herman.

‘All brothers are horrible,’ Hilda said, glaring at Ozan, who waved her book.

They climbed on to the bus, the four children claiming the back seat, and Hal found himself beside Herman. ‘Are you looking forward to the train ride?’ he asked cheerily.

Herman shook his head. ‘The train is taking me to my death.’ He looked at Hal with mournful eyes and whispered, ‘I’m cursed.’

‘Herman, you mustn’t believe in this curse,’ Hal said softly. ‘Arnie is being mean and winding you up.’

‘He isn’t.’ Herman’s grey eyes were wide. ‘Can’t you tell? He’s frightened too.’

Hal paused, realizing Herman was right. ‘How about I promise to protect you?’ he said, poking Ozan and looking at Hilda. ‘We’ll all look out for you, Herman, won’t we?’ They nodded. ‘We are cousins, after all.’

‘Yes,’ Ozan and Hilda replied. ‘Of course.’

Herman pushed his lips into a thin smile.

When they arrived at Berlin Hauptbahnhof station, the family trooped on to an escalator. Hal gazed up through the floors of shops and railway lines, impressed by the futuristic station with its blue glass roof arching high above him like a cresting wave of ice.

The platform was empty but for two middle-aged women standing beside a cat basket. One was dressed in a navy trouser suit and camel-coloured coat, her black hair cropped close to her dark brown skin. The other woman was pale with pink flushed cheeks. Her wavy mane of thick dark hair was streaked with grey and pinned up either side of her head with coral combs. She wore dangly gold earrings, purple eyeshadow and at least five different-length necklaces over a gold-and-black blouse that shimmered beneath her fluffy faux-fur green coat. She looked a little magical.

As the family moved towards them, Hal noticed the eccentric-looking woman nervously take the other’s hand.

Arnie glared at them. ‘Those stupid women are on the wrong platform,’ he said, and marched towards them, his chin jutting forward as he called out, ‘Was denkt ihr, dass ihr hier macht?’

Oliver hurried after Arnie with an apologetic look on his face.

‘Wer von euch ist Clara Kratzenstein?’ the eccentric-looking woman asked, her eyes flitting from Alma to Clara with a questioning look.

‘I am Clara Kratzenstein.’

The woman let go of her friend’s hand and hugged Clara to her. ‘Schwester, mein herzliches Beileid,’ the woman said. ‘Ich bin Freya.’

‘Freya?’ Clara blinked. ‘Alexander’s sister?’

Freya nodded. ‘I’m sorry I did not come to your wedding. If I had, this wouldn’t be so strange.’

‘Aunt Freya?’ Arnie looked confused. ‘You’re coming to Wernigerode?’

‘Yes, young Arnold,’ Freya replied, turning and cupping his cheek with her hands. ‘I haven’t seen you since you were a chubby baby. You look like your father, though I see Bertha in your chin and behind those eyes.’

‘People call me Arnie,’ he said grudgingly.

‘Well, it is nice to see you again, Arnie.’ She looked around. ‘Why are we speaking English?’

‘That’s my fault,’ Uncle Nat said, extending his hand. ‘Nathan Strom. Your second cousin.’ They shook hands. ‘My German is not very good, and my son, Harrison –’ he extended his arm and Hal stepped to his side – ‘speaks no more than a handful of words.’

‘Cousin Freya,’ Alma gushed, hugging her. ‘We can’t have been more than children when last we met, but you haven’t changed.’

The smartly dressed woman had been hanging back, but Freya grabbed her arm and pulled her forward. ‘Alma, everyone, this is Rada, my partner. She’s joining us for the weekend.’

‘Lovely to meet you, Rada.’ Alma hugged her too.

‘Oh, I’m so happy you’re here,’ Clara declared with tear-filled eyes, linking her arm through Freya’s. ‘It will be good to have a sister at Schloss Kratzenstein.’

As Hal watched the women walking down the platform, he realized that Clara was dreading the trip to the house almost as much as Herman.

‘Look there! It’s here!’ Ozan called out as a square sky-blue locomotive, pulling three old-fashioned carriages, approached the platform. The carriages were short, panelled with dark wood and ringed with curling ironwork. One even had a chimney.

‘A Bombardier TRAXX,’ Uncle Nat muttered appreciatively. ‘Electric,’ Hal said, seeing the pantograph that reached up from the top of the train making contact with the overhead power line.

‘Diesel-electric and, I think by the model number, dual-voltage. That loco can travel anywhere.’

‘As long as their wheels match the track gauge,’ Hal added in a knowing tone, and Uncle Nat laughed.

‘Yes, but I’ll bet it has a variable gauge system, so all you’d need to do is to pass through a gauge changer.’

‘The carriages look ancient.’

‘Early 1900s. Wooden, with welded steel underframe. Beautiful. They’re short so they can travel on winding narrow-gauge tracks through mountains.’

Hal wished he could draw the train. Two men in station uniforms began loading their luggage into the end coach, and the train driver had opened his door to talk to Arnie. He was burly, with thick dark brows and hairy arms and hands. He wore charcoal overalls unbuttoned to reveal a plaid shirt and red bandana. Arnie climbed up into the cabin, sitting down beside the driver, and Hal felt a pang of envy.

‘What do you make of Freya Kratzenstein?’ Hal asked his uncle quietly. ‘No one’s mentioned her before. She’s not on my family tree.’

‘She’s Alexander’s sister. There was some falling-out in the family when she was young. The baron must have invited her as a courtesy. I don’t think anyone expected her to show up.’

‘That’s suspicious, don’t you think?’ Hal said. ‘Alexander dies in strange circumstances, his will goes missing and then she suddenly turns up?’

‘It’s certainly interesting,’ Uncle Nat agreed. ‘Come on, we’d better board the train. We’re the only ones left on the platform.’

Ozan and Hilda waved at Hal from a carriage door, grabbing and pulling him on to the train.

‘This way,’ Hilda said.

‘What took you so long?’ Ozan asked.

‘Dad and I were admiring the train.’ Hal turned and Uncle Nat waved at him and went into the next carriage. There’d been a moment on the platform when he’d thought Uncle Nat and he were finally going to talk about their investigation, but again their conversation had been cut short.

‘Herman, how come Arnie gets to ride in the cab with the driver?’ Hal asked, following Ozan into a carriage decorated like a grand office.

‘Aksel Mulch is the groundsman at Schloss Kratzenstein,’ Herman replied, sitting on a sofa. ‘He takes care of Opa’s trains. He’s been at the house since he was a boy. His mother used to be the housekeeper.’ He looked out of the window. ‘But she’s dead now.’

Ozan grimaced at Hal, who struggled not to laugh.

They felt the familiar jerk of the train moving out of the platform, and as it emerged from the shelter of the blue glass roof the grey light of morning flooded the carriage. Picking up speed, they rattled past the tower blocks of Berlin, finally on their way to Schloss Kratzenstein.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

BELLADONNA

Alexander Kratzenstein’s private train told of his pride in the family railway business. On the walls of his travelling office, between windows fitted with wooden blinds, were antique posters celebrating a hundred years of German railways, 1824 to 1924, framed and bolted to the varnished wooden walls. The carriage was stripped of any usual fittings; it had no corridor, and was laid with a thick burgundy carpet. Down the far end was a heavy wooden desk with an anglepoise l

amp and a cast-iron model of a Class 99 steam locomotive on it. Behind it was a high-backed leather chair and a fitted bookshelf that filled the end wall. In the centre of the shelves hung a portrait of Alexander Kratzenstein himself. He looked severe, sour and powerful. Wherever Hal was standing in the carriage, the picture seemed to be looking at him.

The children sat on two sofas facing each other. Between them was a table on which stood the heavy black and white soldiers of a marble chess set. Hal noticed that Herman had chosen to sit with his back to his father’s picture. It occurred to him that Alexander Kratzenstein would have been sitting at his desk only eight days ago, on his way to Schloss Kratzenstein, and he shuddered. He leaned his forehead against the glass of the window, watching the agricultural land of Germany zip by. A rusty mound beside the track caught his eye, and he recoiled at the sight of a dead fox.

‘What is it?’ Herman asked.

‘Nothing,’ Hal replied with a forced smile. ‘I’d love to look at the other carriages in the train. Do you want to show me around?’

Herman paused then shook his head.

Hal nodded, glancing at the empty chair behind the desk, trying to avoid the piercing eyes of the painting. Being on this train was upsetting Herman, and it was creeping him out too. He was beginning to dread what he might find waiting for him at Schloss Kratzenstein.

Ozan jumped up, saying, ‘I’ll come with you,’ and Hal wondered if he too was finding this carriage unsettling.

‘I’ll stay with Herman,’ Hilda said.

‘You can go with them if you want,’ Herman said mournfully.

‘I don’t.’ She held up her book. ‘I want to finish this before Ozan ruins it.’

‘I can tell you the ending right now.’ Ozan grinned.

‘Unless you want to play chess?’ Hilda said to Herman, ignoring her brother.

‘Come on, Ozan.’ Hal went to the carriage door and opened it. There wasn’t a corridor to the next car, but instead an outdoor veranda. The boys exchanged a gleeful look, gripping the railing tightly as they crossed to the opposite platform, buffeted by the wind and exhilarated by the speed of the train.

‘Whoever takes care of these carriages does a good job,’ Ozan shouted. ‘They’re a hundred years old, but nothing rattles.’

Stumbling into the next carriage, they were embraced by warmth and the smell of coffee. The adults all stopped talking and looked at them.

The room in which they found themselves made Hal think of a log cabin. Mounted on the rust-red walls was a glassy-eyed stag’s head. At the far end of the room was a cylindrical wood-burning stove with a silver chimney piping smoke out through the roof, and the floor was covered with a thick patterned rug of russet and gold.

‘Hi,’ he said, conscious that they’d burst in on something they weren’t supposed to hear. He wondered if they’d been discussing the funeral.

There were two upholstered sofas along the far wall. Uncle Nat and Oliver Essenbach were perched on one, Alma and Clara were on the other. The baron was in a chunky wooden armchair opposite them, and Rada in one close to the stove, sipping coffee. Freya was sitting at her feet, with the black cat on her lap, stroking and fussing over it.

‘Is Herman all right?’ Clara asked.

‘He’s playing chess with Hilda,’ Ozan replied. ‘Harrison wanted to look around the train.’

Hal blushed.

‘Harrison,’ Freya said, ‘in this family we’re all train crazy. You must explore every inch of this train if you want to.’

‘Thank you,’ Hal replied gratefully, noticing that Freya was the only grown-up who didn’t look tense or worried. She was smiling warmly at him and her eyes twinkled, and before he’d considered whether it was rude or not he said, ‘Freya, do you believe in the witch’s curse? The Kratzenstein curse, I mean?’

Everyone in the carriage stiffened and looked at her.

‘What is a witch?’ Freya’s voice was husky. ‘That is a good question. Many years ago the Kratzensteins did something terrible, and were cursed for it.’ She paused, drawing in a long breath. ‘Do I believe the words of a curse have the power to kill?’ She slowly shook her head. ‘Words cannot kill on their own.’

‘Please, let’s not talk about the curse,’ Alma said, wringing her hands. ‘My mother was a Kratzenstein.’

‘Don’t be frightened, Oma,’ Ozan said, taking a poker from a hook on the wall and making his way to the wood burner. ‘Science can prove curses can’t hurt you.’ He opened the door and prodded the glowing embers, then put another log in.

‘It hurt my Alexander,’ whispered Clara.

Everybody looked down, not knowing what to say.

Uncle Nat began a quiet conversation with Oliver, in German, and there were no seats free, so Hal went and sat on the floor beside Freya. As he sank down next to her, he inhaled a heady waft of oranges and geraniums.

‘What’s that smell?’ he asked.

‘My perfume,’ Freya replied. ‘You like it?’

‘Yes.’ Hal nodded. ‘What’s your cat’s name?’

‘Belladonna. It means beautiful lady, and she certainly thinks she is one.’

Hal scratched Belladonna under the chin. She turned her amber eyes towards him, half closing them with pleasure. ‘Doesn’t she mind being on a train?’

‘Belladonna doesn’t like to be left behind. She comes with me everywhere.’

‘Isn’t belladonna –’ Hal eyed Freya suspiciously – ‘another name for deadly nightshade?’

‘Very good, Harrison.’ Freya looked delighted. ‘Are you a botanist?’

‘No, I saw it on a TV show,’ Hal admitted. ‘Deadly nightshade is a dangerous poison.’

‘Ja, it can kill you.’ Freya nodded, then leaned forward conspiratorially. ‘Did you know it’s also an important ingredient in the potion used by witches to help them fly?’ She arched an eyebrow and gave a throaty laugh. The cat flinched. ‘Oh, liebling, did I startle you?’ she purred, stroking Belladonna.

Hal stared at Freya, and Rada let out a pshaww! and shook her head. ‘She likes to tease.’ Her sonorous voice was affectionate. ‘Take no notice.’

‘Me? Tease?’ Freya put her hand to her chest and opened her mouth in mock shock.

Hal laughed, and her humorous nature emboldened him to ask the question he really wanted to know the answer to.

‘Why is everyone so surprised to see you here?’

Freya dropped her hand and her mouth snapped shut.

‘I-I mean,’ Hal stammered, realizing he’d asked a sensitive question, ‘it’s not strange that you should want to go to your brother’s funeral.’

After a long pause, Freya answered.

‘I grew up in Schloss Kratzenstein. It’s my home.’ She looked away, remembering a different time. ‘Twenty-eight years ago, when my little brother Manfred died, my mother’s grief ate her up from the inside. She died four years later. My father became controlling. Alexander tried to please him by throwing himself into the family business and marrying the woman my parents thought would make a good match for him.’

‘Arnie’s mother?’

‘Bertha.’ Freya nodded.

‘Alexander was trying to be two sons.’ She sighed. ‘But every choice I have ever made about my life upsets Papa. I am not interested in the railway. I like plants – I wanted to be a botanist.’ She paused. ‘And I wasn’t interested in marrying the men he introduced me to.’ She reached up, taking Rada’s hand. ‘One day, I’d had enough of hiding who I was, and I told my father that I was going to follow my heart.’ She looked down. ‘And he told me to leave and never return.’ After a long pause, she looked into Hal’s eyes. ‘And so, I haven’t.’

Hal was shocked.

‘But now –’ Freya stroked Belladonna – ‘I think it’s time to come home.’

‘Does he know you’re coming?’

‘No.’ She swallowed, and Hal saw that she was nervous. ‘But it was Papa who wrote to me and told me that Alexander had died, so I hope

he will be pleased to see me. After all, I’m his last living child.’

CHAPTER TWELVE

KRATZENSTEIN HALT

‘Enough of my troubles,’ Freya declared. ‘Go and finish your exploration of the train.’ She nodded at the door into the next carriage. ‘There’s a hot-drinks machine in the kitchen.’

Hal got up, tugging Ozan’s sleeve, and the boys crossed the veranda to the third carriage. They were standing in a silver-and-blue kitchenette. Hal opened a door in the middle of the carriage and found a compact bathroom with a shower. At the end was the guard’s room, where their luggage was stored.

‘Want a drink?’ Ozan asked, hitting a button on the fancy coffee machine.

‘Hot chocolate, please,’ Hal answered. ‘Did you hear what Freya said about her dad?’

‘A bit.’ Ozan sounded disinterested. ‘Hey, look, it’s Magdeburg.’ He pointed out of the window as the train crawled through the station. ‘We’re more than halfway there now.’ He opened cupboards until he found cups. ‘I wonder if we’ll be allowed to play with the model trains. Opa says Arnold Kratzenstein’s been building the railway since he was a boy and they run all through the house.’

‘You like model railways?’

Ozan thought before answering. ‘I like models. It’s not about the trains. Small worlds made to a scale are cool.’ They went and sat in the booth opposite. ‘Once, I made this house for Hilda’s dolls, with furniture and everything. I drew the plans to match the scale of her dolls, and constructed the whole thing from boxes.’ He looked out of the window. ‘If old Arnold is kind, he might let us add to his model railway. I could build him a bridge. That would be fun.’

The ominous dragging in Hal’s stomach warned him the weekend was going to be anything but fun. Up ahead, opaque clouds huddled low over distant dark peaks. ‘Is that . . .’

‘The Harz mountains.’ Ozan nodded.

‘What do you make of Arnie’s curse story?’

‘Father told us about the Kratzenstein curse before we came.’

‘Does he believe in it?’

Danger at Dead Man's Pass

Danger at Dead Man's Pass The Highland Falcon Thief

The Highland Falcon Thief Revenge of the Beetle Queen

Revenge of the Beetle Queen Battle of the Beetles

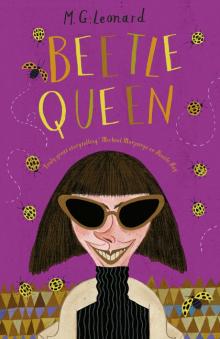

Battle of the Beetles Beetle Queen

Beetle Queen