- Home

- M. G. Leonard

Revenge of the Beetle Queen Page 4

Revenge of the Beetle Queen Read online

Page 4

“Scientific!” Virginia scoffed. “What does that even mean?”

Bertolt started to reply. “I think what he means is—”

“Okay, Einstein.” Virginia put her hands on her hips, cocking her head in mock despair. “I know what he means. I just think …” Her face froze.

“What?” Bertolt frowned. “What is it?”

Virginia looked into Bertolt’s eyes, her face deathly serious, and silently mouthed the words “Don’t move!” She leapt toward him, grabbing his shoulder. Bertolt yelped but held still, looking terrified.

“What is it? What is it?”

“Darkus!” Virginia shouted. “Get me a box, a container, anything! Quick!”

Darkus searched his pockets in a panic and pulled out a clear plastic Tic Tac box, a few brightly colored sweets left at the bottom.

“Pull the lid off,” Virginia instructed, her hands cupped together as she carefully pulled them away from Bertolt. “Empty it.”

Darkus quickly did as he was told and held out the empty container.

“Wow! This thing’s going mental trying to get out,” Virginia said, not taking her eyes off her cupped hands. “Ow! It bit me!”

“What bit you?” Bertolt asked.

“The ladybug.”

Bertolt was shocked. “Ladybugs don’t bite.”

“Well, this one does.”

“Actually, some ladybugs are cannibals,” Darkus said.

“Cannibals?” Bertolt’s eyebrows shot up. “They eat each other?”

“Darkus, I’m going to open a tiny gap between my index and forefinger.” She nodded at the two fingers of her right hand. “Hold the box over the gap.”

Darkus nodded as he placed the clear plastic box over Virginia’s fingers.

“Here goes.” Virginia’s face was so concentrated her eyebrows were touching. She carefully opened up a gap—just a chink—under the plastic container. A black-and-yellow shape shot into the box. “Got you!” she crowed, flipping the box upside down, turning the beetle on its back, and flattening her hand over the top. “Quick, give me the lid.”

Darkus handed the white plastic lid to Virginia and she sealed the container, holding it up so they could all see it.

“It’s a yellow ladybug!” Bertolt said.

“A big one.” Virginia looked at Darkus.

The six-spotted ladybug was angrily throwing itself at the wall of the container, trying to get out.

“She’s watching us!” Darkus hissed.

“Who is?” Bertolt looked from Darkus to Virginia in alarm.

“Lucretia Cutter.” Darkus swallowed, his mouth suddenly dry. “The yellow ladybugs are her spies. Remember, there was one in the entomology vault in the Natural History Museum, when I was looking for Dad?”

Virginia nodded. “From now on, we need to keep our eyes peeled.”

“It was on me?” Bertolt squealed. “Why was it on me?”

“I thought I saw one the other day,” Virginia said to Darkus, “outside the Emporium, but when I looked a second time it had gone.”

“We should stick together,” Bertolt said, clearly shaken, “at all times.”

“Agreed.” Darkus nodded. “I need to get back to Base Camp, make sure Baxter is all right.”

Darkus had been banned from bringing his rhinoceros beetle into school after Baxter had crawled out of his blazer pocket during domestic science and nibbled the bananas laid out to make banana cream pie. When she saw him, the teacher, Mrs. Pavlova, had screamed. Robby, the class bully, had chanted loudly, “Beetle Boy FREAK! Beetle Boy FREAK!” and the other children—the ones who weren’t screaming—had joined in. After that, Darkus had left Baxter in his tank in Base Camp when he went to school.

“Well, I need to go to the library later,” Virginia said, carefully putting the Tic Tac box in her backpack and zipping the pocket closed, “but we should take the ladybug to Base Camp. Keep it there. You can get Baxter at the same time.”

“Why the library?” Darkus asked.

“Benson’s history homework, finding a primary and secondary source of evidence from a real event. I figure the library’s the best place to go. I thought I’d use a newspaper article about Lucretia Cutter.” She grinned. “Doing detective work and homework at the same time.”

“That’s a good idea.” Darkus nodded.

“We can go to the library together.” Bertolt looked hopefully at his friends. “We’ve all got to do Mr. Benson’s assignment, after all.”

“Yeah”—Virginia slung the backpack over her shoulder—“but I’m the one doing Lucretia Cutter. You can’t copy my idea.”

“I’ve found something on the old microfilm viewing thingy, come and see.” Virginia waved her hand in front of the boys’ faces.

Darkus and Bertolt got up from the library computer where they’d been searching the newspaper archive for stories about Lucretia Cutter. The computer archive went back only three years, because the bulk of the historical archive was stored on microfilm and had to be viewed on a special machine, which Virginia had claimed as soon as they’d walked through the doors of the library. The microfilm machine had a large monitor, and below it was Virginia’s chosen microfilm tape, which looked like a ribbon of photograph negatives. As she pressed a red button, the tape was fed underneath a lens and an image appeared on the screen.

Virginia jabbed her finger at it. “Listen to this,” she said. “Spencer Crips, a sixteen-year-old boy from east London, who works as a laboratory assistant at Cutter Laboratories”—Virginia paused, flinging them a look loaded with meaning—“is thought to have tragically drowned in the Camden canal. Police were unable to recover his body, which was swept away into the sewer system, but a pair of his shoes and a watch were discovered on the bank of the waterway. He leaves behind a devastated mother, Mrs. Iris Crips, who asked that we print this statement: ‘Spencer is my life. I don’t believe he has drowned. He’s a good swimmer. Please, if you see him, contact the police.’ Chief Superintendent Suborn said that Mrs. Crips was grief-stricken and, unfortunately, they were certain Spencer Crips had drowned.”

“I don’t understand. What’s that got to do with anything?” Darkus frowned at Virginia. “Other than Spencer What’s-His-Name working for Lucretia Cutter, it’s got nothing to do with the beetles.”

“Don’t you think it sounds a bit odd?” Virginia said. “A pair of shoes, a watch, but no dead body?”

“Maybe he went for a swim in the canal and got dragged under,” Bertolt said.

“Are you kidding me? Have you seen how shallow the canal is? Shopping carts stick up out of it.” Virginia pointed to the screen again. “And look, this article is dated five years ago.”

“So?” Darkus prompted.

“So …” Virginia rolled her eyes impatiently. “Haven’t you ever wondered how long the beetles have been living in their mountain? We know they were born with their special abilities in Lucretia Cutter’s laboratories, but when? And how did they get out of there? Something must have happened for them to end up in the Emporium.”

“Yeah.” Darkus nodded. “That’s true.”

“I think this is it.” Virginia pointed at the picture beside the article. A boy with a friendly crab-apple face, topped by a clump of unkempt fair hair, smiled at them from behind rectangular glasses. “Spencer Crips.”

“What makes you think Spencer Crips has anything to do with the beetles?” Bertolt asked.

“Because I’m a genius.” She tipped her head to one side and smiled. “And I worked out how long the beetles have lived in the mountain.”

“How?” Darkus asked.

“Marvin told me.” She held her hand underneath the hair braid Marvin was clinging to, and the cherry-red beetle dropped down onto his giant black legs. “He doesn’t understand time, so I explained what Christmas is. I showed him the colored lights that are being strung up in our street, and the decorated trees in people’s windows, and he told me he’s seen four Christmases before.”

“He told you that, did he?” Darkus snorted.

“No, smart aleck, obviously not. Marvin can’t talk, he’s a beetle. But he can tap his leg on the table, and that’s how he tells me numbers. He tapped his leg four times—that means Marvin has seen four Christmases. It’s December now, so this will be his fifth Christmas.” She narrowed her eyes and pursed her lips, daring either of them to doubt her.

“That’s pretty clever,” Bertolt said, looking at Darkus.

“Yeah, that’s good,” Darkus admitted.

“I know!” Virginia crowed. “I was looking for something that happened about five years ago that might explain it, but that’s not all … Marvin recognizes him.”

“What!?” Darkus spluttered.

“He got excited when he saw this picture. He dropped onto the screen, and—I swear—he stroked Spencer Crips’s face.”

“Weird,” Bertolt whispered, his eyes wide.

Darkus put his face close to the glass of the screen, leaning his shoulder in so Baxter could see the picture. “Baxter. Do you recognize him? Do you know Spencer Crips?”

The rhinoceros beetle nodded his head.

“See!” Virginia said. “They all know him.”

Darkus looked at Virginia. “But what does this mean?”

“It means we need to visit Mrs. Crips and ask her what she thinks really happened to her son.” Virginia jumped to her feet. “Because I have a hunch that he might still be alive.”

“No!” Bertolt looked horrified. “We can’t ask a stranger about whether her son is dead or not!”

“I can’t go anyway,” Darkus said flatly. “Dad’s forbidden me from doing any detective work to do with Lucretia Cutter.”

“But you’re here looking through articles to do with her.” Virginia put her hands on her hips.

“Yeah, but this is homework for Benson, in the library.” Darkus shrugged, feeling uncomfortable. “It’s safe, and Dad isn’t going to know what articles I was looking at. Going and talking to someone about Lucretia Cutter, that’s definitely forbidden.”

“Oh, come on,” Virginia protested, “this may not have anything to do with Lucretia Cutter, in which case it’ll be fine, and if it does … well, don’t you want to know?”

“Of course I do, but I’m supposed to sit around doing nothing,” Darkus said miserably, “not getting into trouble, or in the way.”

“Doing nothing is the same as helping Lucretia Cutter,” Virginia said. “And what about the yellow ladybug? She’s watching us.”

“Yeah, I know,” Darkus agreed, “which Dad would say was even more of a reason to keep out of trouble.”

“You know what I think?” Virginia said, crossing her arms. “I think this”—she waved a hand at the newspaper article—“is similar to stories I read a couple of months ago, about a scientist who disappeared from a locked vault in the Natural History Museum. The police and the papers said he’d run away or killed himself, and they didn’t want to investigate. They did nothing.”

Darkus’s eyebrows shot up.

“What if this is the same, Darkus?” Virginia said. “What if this is like when your dad disappeared? What if Spencer Crips is alive somewhere? What about Mrs. Crips?”

“But …” Darkus looked at the ground. “I promised Dad.”

“We won’t be going anywhere near Towering Heights. Mrs. Crips lives in Hackney.”

“How do you know that?” Bertolt asked.

“I looked her up in the phone book. Twenty-seven Elton Road.” Virginia grinned, holding up a large blue book that was on the table beside the microfilm viewer. “C’mon, Darkus,” she pleaded. “Your dad couldn’t mind us going to talk to an old lady who’s probably never even met Lucretia Cutter.”

“We could ask him,” Bertolt said helpfully.

Virginia slapped his arm. “No, we couldn’t.”

Darkus thought about all the rules he’d had to obey since his dad had got out of the hospital. He wouldn’t actually be disobeying any of them directly. “I suppose it’s not really to do with Lucretia Cutter …”

“We may not even find out anything,” Virginia coaxed.

“Oh, all right!” Darkus threw his hands up. “I’m sick of sitting around and waiting for someone to tell me what’s going on. Let’s do it.”

“Yes!” Virginia punched the air. “I say we visit Mrs. Crips now. We can take the bus—it’s about twenty minutes away.”

“If we find out anything important,” Darkus said, feeling a surge of excitement, “we can tell Dad and Uncle Max and show them the yellow ladybug.” He smiled. “Then Dad will see that I can help.”

Number 27 Elton Road stood out from its neighbors like a rotten incisor in a line of pearly-white teeth. The cracked paving in the tiny front garden was choked with ivy and dandelions, and the path up to the front door was clogged with chip bags and sweet wrappers. Darkus noticed the curtains were drawn.

“This building looks sad,” Bertolt whispered.

“Baxter, you’re going to have to hide,” Darkus told the rhinoceros beetle. “You too, Marvin, and you, Newton.”

Baxter crawled into the neck of Darkus’s green sweater, Newton disappeared into Bertolt’s thicket of white hair, and Marvin curled himself up around the end of one of Virginia’s braids.

“C’mon.” Virginia knocked on the door loudly and pushed Bertolt forward. They had decided that, as Bertolt was the neatest and least frightening, he should do the talking.

They waited for Mrs. Crips to open the door.

“Shall I knock again?” Virginia whispered, and then a click sounded, and the door opened a sliver.

An eye and a nose, framed by curly gray hair, peeped through the gap. The eye blinked. “Yes? Who is it?”

Virginia poked Bertolt in the back.

“Good day, Mrs. Crips. We are sorry to bother you,” Bertolt said politely. “My name’s Bertolt, this is Virginia, and this is Darkus. We know it’s a terrible imposition to ask, but we were wondering if we could talk to you about Spencer?”

Mrs. Crips opened the door a little wider. She was a small woman, shrunken by a stooped back and rounded shoulders. She wore a black dress, and her springy gray curls were tangled and uncared-for, but she had a kind face, and its deep lines suggested she had smiled a lot in her past.

Her scraggly eyebrows rose as Bertolt haltingly explained that they were detectives and had come across Spencer’s story in the library, that they felt his case hadn’t been properly investigated by the police, and that—with her permission—they’d like to do a bit of investigating of their own.

“Of course,” Bertolt added, blinking, “if you’d rather not talk about it we’d quite understand—”

“You see,” Virginia interrupted, “we think Spencer may still be alive.”

Mrs. Crips’s face brightened and she let the door swing open. “You’ve no idea how long I’ve waited for someone to say those words. Come in, come in.”

The square hallway opened out into a dingy living room. Beyond it, Darkus could see a beige kitchen and cork-tile flooring. Along the long left wall of the living room was a thin shelf that stepped up over an old electric fireplace to become a mantelpiece and stepped down again on the other side, becoming the top of a bookshelf. The shelf was stuffed with framed photographs, as were the side tables that hovered beside the two armchairs sitting on either side of a grubby circular rug. The pictures were all of Spencer: Spencer building a sandcastle, Spencer’s school photos, Spencer straddling a bicycle. In one picture Spencer was a happy-toothed toddler holding his mother’s hand. Mrs. Crips was young and smiling, a homely woman in a flowery dress, her unruly hair pinned up, one caramel-colored curl flying free in the wind.

Standing in the darkened room, Darkus could feel how desperately Mrs. Crips missed her son. He sat down on one of the arms of the big chairs, suddenly feeling the weight of how much he missed his own mother.

“Look.” Virginia elbowed him and pointed at a picture hanging on the wall ab

ove the fireplace. A skinny teenage Spencer in a white lab coat, his hands balled up in his trouser pockets, was looking adoringly through rectangular spectacles at an enormous dung beetle sitting on his shoulder.

Darkus gasped.

In the kitchen, Mrs. Crips filled her kettle and took out porcelain teacups. “I had a packet of biscuits in here somewhere,” she said, opening and closing cupboards.

“Don’t worry,” Bertolt said. “We’ll manage just fine without them.”

“Oh no, I insist. It’s not every day I have visitors who want to talk about Spencer.”

Once the kettle had boiled, Bertolt lifted it and poured water into the waiting teapot. “We really don’t want to be any trouble.”

“No, no, no trouble at all,” Mrs. Crips said, her head inside a cupboard. “My Spencer loves to dunk a biscuit in a cup of tea. Here we are now.” She turned around with a packet in her hand. “I knew I had some.”

“I”ll carry it,” Bertolt insisted as she loaded the teacups onto a floral tea tray.

Mrs. Crips pulled a small side table between the two armchairs. “Set it down here—Bertolt, is it?—thank you.”

Mrs. Crips sat down opposite Darkus with a happy sigh. “I can’t remember the last time I had a conversation with anyone other than the postman,” she said, looking at the three children. “Now, why don’t you tell me what it is that you want to know about my Spencer?”

“I read in the paper, Mrs. Crips”—Virginia paused, and Darkus wondered what was going to come out of her mouth—“that you think Spencer … um, that perhaps he didn’t drown like the police said?”

“No. Spencer would never drown,” Mrs. Crips replied with certainty. “He was a good swimmer and the canal is shallow.”

“But what about the shoes and his watch?” Virginia asked.

“Pooh!” Mrs. Crips’s face scrunched up like she had smelled something bad. “I don’t know why that appeared in the papers.” She shook her head. “It’s rubbish.”

Danger at Dead Man's Pass

Danger at Dead Man's Pass The Highland Falcon Thief

The Highland Falcon Thief Revenge of the Beetle Queen

Revenge of the Beetle Queen Battle of the Beetles

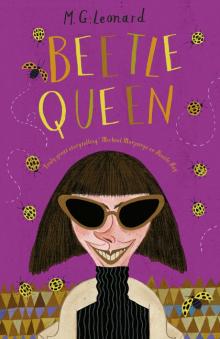

Battle of the Beetles Beetle Queen

Beetle Queen