- Home

- M. G. Leonard

Beetle Queen Page 22

Beetle Queen Read online

Page 22

‘After Prague,’ Uncle Max said, ‘Motticilla and I will be leading a rescue mission to the Amazon. We’re going to find Barty, Spencer and Novak and bring them home – and, whilst we’re at it, do a bit of giant insect hunting.’ He waggled his eyebrows.

‘YES!’ Virginia leapt to her feet and punched the air. ‘Another adventure.’

‘Hush now. Sit down, Virginia,’ Barbara Wallace said. ‘I’ve had enough talk of adventure.’

Bertolt got to his feet. ‘I don’t like adventures. Not one bit.’ He turned to his mum. ‘But I have to help Novak. She needs us.’

‘Oh, c’mon, Mum!’ Virginia protested. ‘You saw Lucretia Cutter on TV. Imagine what she’s going to do to Novak for helping us. You’ve got to let me go.’

The flickering firefly and the cherry-red frog-legged leaf beetle rose into the air, hovering above their humans’ heads.

‘Today is Christmas Day.’ Barbara Wallace held up her hands. ‘Why don’t you children each open a present?’ She gestured to the mound of gifts under the tree. ‘How about that red one, Virginia? That’s for you. Bertolt, Darkus, yours are the ones with stars on.’

Sulkily, Virginia got down on her knees and pulled out the red present from under the stack of gifts stuffed under the heavily decorated tree. She handed Bertolt and Darkus their presents and looked at her mum for permission to open hers. Barbara Wallace nodded, and Virginia half-heartedly ripped off the paper, pulling out a pair of camo trousers and a small bag, in camo fabric, stuffed full of things.

‘Oh wow!’ She pulled open poppers and undid the zips in the bag, emptying on to the floor a compass, a Swiss army knife, a mosquito net, a set of waterproof matches, a tiny first aid kit, a reel of string and water purifying tablets. She looked up at her mum. ‘This is amazing!’

Darkus and Bertolt ripped open their presents to find they each had a small camo bag stuffed with the same things.

‘Well, I thought they would be useful,’ Barbara Wallace nodded, ‘if you’re going to the Amazon jungle.’

‘You’re going to let me go?’ Virginia jumped to her feet, flying at her mother, arms wide. She hugged her tightly.

‘The compass is so that you can always find your way home,’ Barbara Wallace said, stroking Virginia’s head.

‘Oh, thank you, Mum, thank you, thank you.’ Virginia kissed her mother’s forehead and cheeks.

Bertolt turned to his mother, and she nodded. ‘I saw that Lucretia woman with my own eyes. She needs to be stopped.’ Calista Bloom smiled proudly. ‘And I think you’ll do better if I don’t come this time.’

‘The Amazon!’ he whispered breathlessly, looking at Darkus.

Darkus nodded. ‘It’s time someone stood up to Lucretia Cutter and made her realize this world does not belong to her.’

AN ENTOMOLOGIST’S DICTIONARY

abdomen

the part of the body behind the thorax (human abdomens are usually referred to as tummy or belly). It is the largest of the three body segments of an insect (the other parts being the head and the thorax).

antennae (singular: antenna)

a pair of sensory appendages on the head, sometimes called ‘feelers’. They are used to sense many things including odour, taste, heat, wind speed and direction.

arthropod

means ‘jointed leg’ and refers to a group of animals that includes insects (known as hexapods), crustaceans, myriapods (millipedes and centipedes) and chelicerates (spiders, scorpions, horseshoe crabs and their relatives). Arthropod bodies are usually in segments, and all arthropods have an exoskeleton and are invertebrates.

beetle

one type (or ‘order’) of insect with the front pair of wing-cases modified into hardened elytra. There are more different species of beetle than any other animal on the planet.

chitin

the material that makes up the exoskeletons of most arthropods, including insects. Chitin is one of the most important substances in nature.

coleoptera

the scientific name for beetles.

coleopterist

a scientist who studies beetles.

compound eyes

can be made up of thousands of individual visual receptors, and are common in arthropods. They enable many arthropods to see very well, but they see the world as a pixelated image – like the pixels on a computer screen.

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid)

the blueprint for almost every living creature. It is the molecule that carries genetic information. A length of DNA is called a gene.

double helix

the shape that DNA forms when the individual components of DNA join together. It looks like a twisted ladder.

elytra (singular: elytron)

the hardened forewings of beetles that serve as protective wing-cases for the delicate, membranous hind wings underneath, which are used for flying. Some beetles can’t fly; their elytra are fused together and they don’t have hind wings.

entomologist

a scientist who studies insects.

exoskeleton

an external skeleton – a skeleton on the outside of the body, rather than on the inside like mammals. Insects have exoskeletons made largely from chitin. The exoskeleton is very strong and can be jam-packed with muscles, meaning that insects (especially beetles that have extremely tough exoskeletons) can be very strong for their size.

habitat

the type of area in which an organism lives – for example, a stag beetle’s habitat is broad-leaved woodland.

insect

in the ‘class’ insecta, with over 1.8 million different species known and more to discover. Insects have three main body parts: the head, thorax and abdomen. The head has antennae and a pair of compound eyes. Insects have six legs and many have wings. They have a complex life cycle called metamorphosis.

invertebrate

an animal that does not have a spine (backbone).

larvae (singular: larva)

immature insects. Beetle larvae are sometimes called grubs. Larvae look completely different to adult insects and often feed on different things than their parents, meaning that they don’t compete with their parents for food.

mandibles

beetles’ mouth parts. Mandibles can grasp, crush or cut food, or defend against predators and rivals.

metamorphosis

means ‘change’. It involves a total transformation of the insect between the different life stages (egg, larvae, pupae and adult or egg, nymphs and adult). For example, imagine a big, fat, cream-coloured grub: it looks nothing like an adult beetle. Many insects (including beetles) metamorphosize inside a pupa or cocoon: they enter the pupa as a grub, are blended into beetle soup, re-form as an adult beetle and break their way out of the pupa. Adult beetles never moult and, because they are encased in a hard exoskeleton that doesn’t stretch or grow, they can never grow bigger. Therefore, if you see an adult beetle, it can never grow any bigger than it is.

palps

a pair of sensory appendages, near the mouth of an insect. They are used to touch/feel and sense chemicals in the surroundings.

setae (singular: seta)

tiny hair-like projections covering parts of an insect’s body. They may be protective, can be used for defence, camouflage and adhesion (sticking to things) and can be sensitive to moisture and vibration.

species

the scientific name for an organism; helps define what type of organism something is, regardless of what language you speak. For example, across the world, Baxter will be known as Chalcosoma caucasus. However, depending on what language you speak, you will call him a different common name. The species name is always written with its ‘genus’ name in front of it and it is always typed in italics, with the genus starting with a capital letter and the species all in lower-case type. If you are writing by hand, it should all be underlined instead of italicized. See ‘Taxonomy’.

stridulation

a loud squeaking or scratching noise made by an inse

ct rubbing its body parts together to attract a mate, as a territorial sound or warning sign.

taxonomy

the practice of identifying, describing and naming organisms. It uses a system called ‘biological classification’, with similar organisms grouped together. It starts off with a broad grouping (the ‘kingdom’) and gets more specific, with the species as the most specific group. No two species names (when combined with their genus) are the same: kingdom → phylum → class → order → family → genus → species. This system avoids the confusion caused by common names, which vary in different languages or even different households. For example, Baxter is a species of rhinoceros beetle: some people may call him an Atlas beetle, Hercules beetle or unicorn beetle, and there are lots of different species of rhinoceros beetle. So how do we know what Baxter really is? If you use biological classification, you can classify Baxter as: kingdom = animalia (animal) → phylum = arthropoda (arthropod) → class = insecta (insect) → order = coleoptera → family = scarabaeidae → genus = Chalcosoma → species = caucasus. But all you really need to say is the genus and species, so Baxter is: Chalcosoma caucasus.

thorax

the part of an insect’s body between the head and the abdomen.

transgenic

an animal can be described as transgenic if scientists have added DNA from another species.

Acknowledgements

There is a triumvirate of angels without whom I could not be an author. I want to thank my husband, Sam Sparling, for the personal sacrifices he’s made for my writing career. He is my first reader, greatest cheerleader and trusted partner in crime. Thank you to my dear friend Claire Rakich, beta reader extraordinaire. Her honesty, feedback and enthusiasm helped steer this story and all my stories. Special thanks to Jane Sparling, my mother-in-law, Nana Jane to my children, and the most generous and kind person I know. Without these three angels Beetle Queen would be sitting on my desktop half-written.

I owe an immeasurable debt of thanks to Dr Sarah Beynon, scientific consultant for this trilogy of books. She has helped me get over my fear of insects, letting me hold my first beetle, and become a great friend. If you love beetles you should visit The Bug Farm, Sarah’s wonderful visitor attraction in Pembrokeshire, where you can handle insects and learn all about the little creatures that run the planet. More information here: www.drbeynonsbugfarm.com

Huge thanks to the National Theatre for granting me a sabbatical, and especially Alice King-Farlow, who has been generous and understanding about every single thing. 2016 would have been a different experience without your support, Alice.

I want to thank my kick-ass agent, Kirsty MacLachlan, and everyone at Chicken House. Jazz, Esther, Laura, Sarah and Kes, you are all awesome. Elinor Bagenal, I’m secretly in love with you, but you probably knew that. Thank you for sending the beetles out into the world and finding homes in over thirty countries. Thanks to my trusted editor Rachel Leyshon, I hope you edit every single book I ever write. Thanks to Rachel Hickman for the amazing cover, and artwork for both books, which has made people pick them up and take a risk on an unknown author. I must thank the power-house that is Liz Hyder, a truly passionate and wonderful communicator, and a giant thank-you to Nick and Lori at Scholastic USA, Anja at Chicken House Germany, and all the wonderful people working in publishing companies around the globe bringing beetles into young people’s lives.

Barry Cunningham, you are the ultimate beetle champion. I never take your generosity for granted. A big heartfelt thank-you for everything you have done, and continue to do, for me and the beetles.

I would like to thank the Royal Entomological Society, and the entomological community, for embracing, celebrating and supporting Beetle Boy, and forgiving me my fear of insects. In particular I would like to thank Peter Smithers, Simon Leather, Luke Tilley, Patrice Bouchard and Max Barclay for their support and friendship; you are all heroes in my eyes.

My final thanks goes to you, the reader, and anyone who’s written blog posts, reviews on Amazon, recommended my books, or given them as gifts, and especially to Michael Morpurgo for the quote on the cover. You are all wonderful.

A heartfelt thank you, from me and your coleopteran friends.

If you want to do more, go to www.buglife.org.uk and get involved with the only organization in Europe devoted to the conservation of all invertebrates, everything from beetles to bees.

M. G. Leonard has a first-class honours degree in English Literature and an MA in Shakespeare Studies from King’s College London. She works as a freelance Digital Media Producer for clients such as the National Theatre and Harry Potter West End, and has previously worked at the Royal Opera House and Shakespeare’s Globe. Leonard spent her early career in the music industry running Setanta Records, an independent record label, and managing bands, most notably The Divine Comedy. After leaving the music industry, she trained as an actor, dabbling in directing and producing as well as performing, before deciding to write her stories down. Leonard lives in Brighton with her husband, two sons and her pet rainbow stag beetle.

www.mgleonard.com @MGLnrd

TRY ANOTHER GREAT BOOK FROM CHICKEN HOUSE

WHO LET THE GODS OUT? by MAZ EVANS

When Elliot wished upon a star, he didn’t expect a constellation to crash into his dung heap. Virgo thinks she’s perfect. Elliot doesn’t. Together they release Thanatos, evil Daemon of Death. Epic fail.

The need the King of the Gods and his noble steed. They get a chubby Zeus and his high horse Pegasus.

Are the Gods really ready to save the world? And is the world really ready for the Gods?

‘. . . lashings of adventure, the Olympic gods as you’ve never seen them before and a wonderfully British sense of humour.’

FIONA NOBLE, THE BOOKSELLER

Paperback, ISBN 978-1-910655-41-2, £6.99 • ebook, ISBN 978-1-910655-64-1, £6.99

Text © M. G. Leonard Ltd 2017

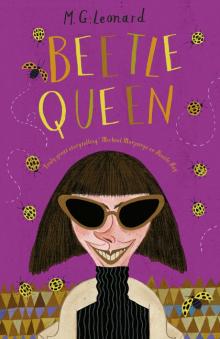

Cover illustration © Elisabet Portabella 2017

First paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2016

This electronic edition published in 2016

Chicken House

2 Palmer Street

Frome, Somerset BA11 1DS

United Kingdom

www.chickenhousebooks.com

M. G. Leonard Ltd has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical or otherwise, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express prior written permission of the publisher.

Produced in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Cover and interior design by Helen Crawford-White

Cover, chapter head and beetle illustrations by Elisabet Portabella

Interior illustrations by Karl James Mountford

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data available.

PB ISBN 978-1-910002-77-3

eISBN 978-1-911077-37-4

filter: grayscale(100%); " class="sharethis-inline-share-buttons">share

Danger at Dead Man's Pass

Danger at Dead Man's Pass The Highland Falcon Thief

The Highland Falcon Thief Revenge of the Beetle Queen

Revenge of the Beetle Queen Battle of the Beetles

Battle of the Beetles Beetle Queen

Beetle Queen