- Home

- M. G. Leonard

Danger at Dead Man's Pass Page 12

Danger at Dead Man's Pass Read online

Page 12

‘Stop,’ Ozan whispered, grabbing the back of Hal’s anorak and pulling him to the ground. He put his finger to his lips, then pointed.

Peering through the snow-covered undergrowth, Hal saw a figure in a black hooded cloak, three or four metres away, squatting down beside a fallen tree, studying its mossy, ivy-clad roots. His heartbeat pulsed in his ears. He saw a pair of hiking boots poking out from the bottom of the cloak. As the figure straightened up, it drew a wooden-handled knife, gripping it in their right hand.

Hal held his breath, squashing himself down into the snow.

A sound of snapping sticks and footsteps caused the cloaked figure to turn, and the hood fell back.

‘Freya!’ Ozan whispered in horror.

Rada came over to her, carrying a basket stuffed with bark, evergreen twigs and pine needles. Sitting in the basket, playing with a twig, was Belladonna. The two women exchanged whispered words. Freya cut something from the fallen tree. Straightening up, Freya added whatever it was she’d removed from the tree into the basket, stroking the cat before slipping her arm through Rada’s. The boys watched them walk away.

‘What did they say?’ Hal asked Ozan.

‘Freya said the snow made harvesting difficult and they should have done this last time they were here.’

‘But Freya told us she hasn’t been back to Schloss Kratzenstein for years.’

Ozan shrugged. ‘Then she said they must go to the stream, to get water.’

Hal was baffled as to what any of this could mean.

‘Do you think Freya kicked those stones down on Dead Man’s Pass? Is she the witch?’ asked Ozan.

‘I don’t know.’ Hal thought of the strange copper pot in her room.

‘What should we do?’

‘Can you follow Freya and Rada, from a distance, and listen to what they’re saying?’ Hal asked. ‘I want to go back to the pass and check something.’

‘Ja.’ Ozan jumped up, excited by idea of tailing Freya and Rada. ‘Meet you in the Kinderturm.’

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

RATTED OUT

Hal waited till Ozan was out of sight before he pulled his pocketbook out. Flipping to a clean page, he drew the crouched, hooded form of Freya, her boots peeping out from her cloak, her knife in her hand. She had lied when she’d said she’d not been home for years. Why? When was she last here? Was it the weekend Alexander had died? Holding his sketch at arm’s length he realized it looked as if he’d drawn a witch. He inspected the fallen tree to see what she had been sawing at with her knife and found a sheared-off nub with some traces of tree sap. He placed his foot beside her footprints in the snow. Freya’s feet were the same size as his. It couldn’t have been her that he’d seen looking down on Dead Man’s Pass.

Making his way round to the far entrance of Dead Man’s Pass, Hal returned to the spot where he’d looked up to see the whirling grey cloak. He scoured the full length of the cutting, hunting for any clue that might shed light on who’d created the rockfall. All he found was a new set of man-sized footprints through the cutting.

‘Hey, Skull Face,’ Hal said to the vacant stone eyes looking down at him. ‘Did you see what happened the night Alexander died? If only you had a jaw, you could tell me.’ Then he had an idea. Grabbing an edge of rock, Hal put his foot into a niche, and climbed up until he could see into the gaping eyeholes.

Reaching into the left eye socket, Hal pulled out the charred circular stump of a big candle. There was one in the right eye socket too. Thinking back to what Herman had said, he wondered if they were left there from Halloween, or were they new? Brushing the snow off the ridge of rock that made the nose, he worked his fingers into the cracks, and reached into the two joined holes that made the skull’s nostrils. His fist touched something soft and he snatched his hand back with a gasp.

Peering into the dark cavity, he saw nothing. Steeling himself, he pulled on his glove and shoved his hand back into the hole, swiftly yanking out whatever it was inside, overbalancing and jumping down to the ground.

In his hand was a small silky black bag. He loosened the drawstring and pulled out two circular discs, one of white face paint, one of black. Staring at the pancakes of paint, his skin prickled. He felt certain this was a clue relating to Alexander’s death. He returned the make-up to its hiding place and jumped down to the ground, pulling out his pocketbook. He drew the skull face, marking where he’d found the candle stubs and the make-up. Then went and cleared the stones away from the railway tracks. The funeral train would be travelling through the pass tomorrow morning and he didn’t want there to be an accident.

Hearing a high mournful whistle, Hal felt a dart of joy and ran to the end of the pass, where he could see the Brockenbahn line. The chuffing of the approaching steam engine, and oyster-grey plume of smoke from the chimney, came before the imposing black-and-red glossy face of the locomotive he’d seen in Wernigerode the previous day.

Running parallel with the track, Hal raced the train up the Brocken until he ran out of puff and had to stop. The train rattled past him, and the driver tooted the whistle as Hal waved.

Up ahead, the train slowed, and Hal saw that beyond the point where the Kratzenstein spur met the main line there was a low wooden platform with a bench and a shelter. It was a station, and sitting on the bench was a man Hal recognized. It was Uncle Nat.

Instinctively, Hal stepped back from the tracks, hiding in the shadow of the trees. He approached stealthily. What was Uncle Nat doing at the station? Was he going to catch the train?

The train stopped. Carriage doors clicked open and slammed shut. A handful of hikers alighted, but Uncle Nat remained on the bench.

The train left, huffing gouts of smoke into the misty air as it continued its climb up the Brocken.

Uncle Nat got up, walking along the platform to a noticeboard, which he appeared to read as the hikers disappeared along the trail into the woods. Then he went to the very end and stooped to tie his shoelace. He straightened up, checked his watch, stepped down from the platform, and Hal watched him walk along the rails back towards Schloss Kratzenstein.

Waiting until he was certain his uncle had gone, Hal crossed the hiking trail on to the small station. He sat on the bench where Uncle Nat had sat, looking all around it, then peered up and down the tracks. He went to the noticeboard. Everything was in German except one English announcement about a change of timetable in the tourist season. Hal went to the end of the platform beside the low wooden fence, where his uncle had tied his shoelace, and crouched down beside frozen leaf mulch and snow. He slipped his fingers under the icy disc of rotten leaves, lifting it up. He cried out, letting it drop. Beneath it was a dead rat with milky white eyes.

Hal looked about, trying to ignore the rat’s grey tail, which was sticking out. Why would Uncle Nat walk to this station, watch a train pass, read a German noticeboard, tie his shoelace next to a dead rat, and then go back to the house? He was missing something. He looked at the grey tail. Was the rat here to put people off looking? Pulling on his gloves, he lifted the leaf mulch again, picking the rat up by its tail. Keeping it at arm’s length, he poked about in the snow, but there was nothing there.

The rat dangling from his thumb and forefinger was surprisingly light. Peering at it, he noticed a thin line, as if made by a scalpel blade, under the rat’s neck.

‘When is a rat not a rat?’ he whispered, putting it on the ground and pulling at the line. It came apart, and Hal saw it was kept closed by a thin strip of Velcro. His heart skipped. Inside, where the rodent should have had a stomach, there was a small scroll of paper. Hal looked over his shoulder, scanning the trees. Had Uncle Nat put the paper in the rat? He took it out and unravelled it. Written on it was a message in pencil that made no sense. It was a sequence of letters and numbers. It was in code.

Pulling out his pocketbook, Hal copied down the code. He shoved the book back in his pocket and returned the note to the cavity inside the rat as quickly he could. His hands were shaking. He k

new he was doing something that he shouldn’t, that he’d discovered something Uncle Nat didn’t want him to know about. He sealed the rat and slid it back under the frozen leaf mulch. Getting up, he tried to look nonchalant as he sauntered back down the platform and dropped down on to the tracks. Out out of the corner of his eye, in the shadow of the trees, he thought he glimpsed a woman with dark eyes watching him. He was unable to stop himself from breaking into a run.

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

BEAR FRUIT

Hal ran up the steps to the front door of Schloss Kratzenstein. It wasn’t locked. Once inside the grand entrance hall, he stopped to catch his breath. He heard a series of high musical notes, and the hairs on the back of his neck rose. He scolded himself for having the heebie-jeebies. The music was someone playing the piano, probably Herman. He told himself that no one had been watching him back at the station. He’d imagined it. His eyes came to rest on a door under the stairs, and he remembered Herman saying it was a bathroom. He needed somewhere private to sort through the maelstrom of thoughts thundering around his head.

Pushing open the door, Hal gave a strangled squeal of fright and his knees buckled as he stared up into the black eyes of an eight-foot bear, standing on its back legs, baring its teeth, its paws raised and claws out. Slumping against the wall, his hand over his hammering heart, Hal inwardly cursed old Arnold for his taxidermy tricks. He locked the door, pulled out his pocketbook, put down the lid of the toilet and sat staring at the note that he’d hurriedly copied down.

It had been written by his uncle – Hal recognized the handwriting. But what did it mean? He hoped, by looking at the letters and numbers, that he might see a pattern or glean some crumb of understanding from them, but ten minutes passed and he was still clueless. Who was Uncle Nat leaving coded messages for? Was he somehow mixed up in what had happened to Alexander Kratzenstein? Was this something to do with the baron and HANGMAN?

‘I need Hilda,’ Hal muttered. ‘She’ll know how to read this.’

Getting to his feet, he went to the sink and splashed cold water on his face. He needed to calm down and focus. He knew that things were often most confusing immediately before a truthful picture started forming in his head. He realized he was hungry. He hadn’t had breakfast. No one could think properly with an empty stomach.

He made his way through the covered courtyard and the salon to the kitchen. A selection of breakfast meats, cheeses and bread had been left on the table, along with a stack of glasses and a jug of orange juice. He grabbed a roll, filling it with salami and cheese. As he ate, he went to the back door, curious about what was on the other side. He found a walled kitchen garden that led to the impressive greenhouse. He saw a gate in the brick wall and crossed the unblemished snow to open it. It led to the railway platform. On the tracks he saw a lone black carriage. The door handles were polished silver, the windows were dressed with black lace curtains, and Hal understood immediately that this was the Kratzenstein funeral carriage. From inside, he could hear the high, gentle sobs of a woman, and knew he shouldn’t be listening to this intensely personal expression of grief. Feeling like a trespasser, Hal crept back through the gate, closing it silently, and returned to the kitchen, picking up more food from the table before making his way to the tower.

Hilda was on her own, reading.

‘Where’s Herman? Is he OK?’ Hal asked.

‘He went to play the piano. He said it calms him down. He’s frightened, because of the accident with the sledge, but he doesn’t want us to tell the grown-ups. He doesn’t want to make a fuss before the funeral or to worry his mum.’

Hal wondered if it was Clara he’d heard crying in the funeral carriage.

‘You’re his hero.’ Hilda grinned.

‘Harrison!’ Ozan burst through the door, breathless, carrying a boot and a shoe. ‘You’ll never guess what I have discovered.’

‘What’s going on?’ Hilda asked, looking from Ozan to Hal.

‘We’ve been detectives,’ Ozan replied.

Hilda crossed her arms angrily. ‘You said being a detective was boring! It was my idea to investigate the curse. This is my case.’

‘We can’t help it if we keep discovering clues.’ Ozan laughed at Hilda’s scowl.

Hal could see they were about to argue. ‘Hilda, when Ozan and I went to the train shed this morning to get the sledges, we saw Aksel’s locket, the one Connie told us about.’

‘It has the initials GB on it,’ Ozan blurted out.

The frown lines disappeared from Hilda’s forehead as her eyebrows lifted. ‘Gobel Babelin?’

Ozan nodded. ‘We think Aksel could be related to the witch!’

‘I asked him what he thought had happened to Alexander,’ Hal told her. ‘He said the Kratzensteins must pay.’ Hilda’s eyes grew wide.

‘Then we searched Alexander Kratzenstein’s desk in the train carriage,’ Ozan said.

‘But we didn’t find the missing will,’ Hal assured her.

‘And after Hal and Herman were nearly killed—’

‘We wouldn’t have died,’ Hal interrupted.

‘You don’t know that,’ Ozan replied, enjoying the drama. ‘Hilda, we went up on to the top of the pass and we found footprints. Then we saw Freya and Rada, so I followed them.’ He turned to Hal, looking like he might burst with what he had to say. ‘They rented a house in Wernigerode a month ago. They were here at the time Alexander died. Freya told Rada that she wished she had talked to her brother before he died. Then they discussed some plan they have, although they didn’t say what it was.’

‘Hilda,’ Hal smiled sweetly at her. ‘We’re going to need your help if we are to make sense of any of this. You know so much about detecting.’

Hilda’s glowering expression softened, her curiosity eclipsing her anger. ‘Why are you holding a boot and a shoe?’ she asked her brother.

‘I followed Freya back to the house. She took her boots off and left them in the cloakroom.’ He held up the boot. ‘Look, it’s too small to have made the footprints we found at the top of Dead Man’s Pass.’ He held up the shoe. ‘But this shoe looks about the right size.’

‘Hang on, I need my glasses,’ Hal said, pulling out his pocketbook. He went to his bed and put them on, flipping the pocketbook so that they wouldn’t see any of his other drawings, just the page with the two footprints. ‘Put Freya’s boot down on the floor.’ Ozan did, and Hal put his foot beside it. Freya’s boot was the same size as his. ‘Now try the shoe.’ Ozan lifted the boot and put down the shoe beside Hal’s foot. Hal held out the drawing so they could all see it.

‘The shoe does look roughly the same size as the footprint,’ Hilda said, ‘but it’s hardly a match.’

‘That’s because the print was made by a boot still on the foot of the person who made it.’ Ozan said, picking up the shoe and gave them a meaningful look. ‘This is Aksel’s shoe. I bet that print was made by Aksel’s boot.’

‘You think Aksel sent the stones crashing on to Hal and Herman?’ Hilda looked alarmed.

‘Yes. He’s related to Gobel Babelin and taking her revenge,’ Ozan said dramatically.

‘Let’s not jump to conclusions,’ Hal said. ‘I wonder why Freya hasn’t she told anyone she was in Wernigerode when Alexander died?’

‘And why is she making strange potions with wild plants and stream water –’ Ozan looked at each of them – ‘like a witch?’

‘This is a real mystery,’ Hilda said excitedly, ‘and we’re going to solve it!’

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CRYPTANALYSIS

‘Hilda, can you help me?’ Hal sat down on the bed opposite her.

‘Is it about the case?’ Hilda looked up from her journal, where Hal could see she’d been scribbling a list in German.

‘No,’ Hal said apologetically. ‘I told my dad what you said about language being a type of code and he set me a puzzle.’ Hal showed her the message he’d found hidden inside the rat. ‘I think he wants me to decode it, but I

don’t know how.’

Hilda studied the page. ‘Is this all he gave you?’

‘Yes.’

‘This looks like a cipher, rather than a code.’ Seeing the puzzled look on his face, she explained. ‘A cipher is when letters are encrypted separately. In a code, whole words are encrypted and can be represented by symbols or other things.’ She looked back at the page. ‘This is almost impossible to work out if you don’t have the key. You could look for patterns, like repeated words or single letters. Look here.’ She pointed. ‘This N is on its own. N is probably an I or an A – they’re the only letters in English that can be a whole word by themselves. And here and here, T2EO is repeated. But . . .’ She shook her head. ‘There are infinite possibilities.’

‘Maybe that’s the puzzle – I have to guess what the key is. What kinds of things can be keys?’

‘A key can be anything that tells the writer and the reader which letters or numbers to swap in for the alphabet.’ Her face lit up. ‘Look, the message starts with a number: 3956-7.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘If a book is used as a key, a number at the start could indicate the page the key is taken from.’ She frowned. ‘But it would be a very large book if it had three thousand, nine hundred and fifty-six pages.’ The excitement sluiced away as she realized that she couldn’t be right. ‘I don’t know,’ she said, handing back the pocketbook. ‘I think your dad made the puzzle too hard. Why don’t you ask him for a clue?’

‘I think I will,’ Hal said, walked as casually as he could to the tower door, but neither Hilda and Ozan showed a flicker of interest. They were both intent on being the first to solve the mystery of the curse.

When Hal got to Uncle Nat’s bedroom door, he knocked and waited.

‘Hello, Harrison.’ Hilda and Ozan’s dad was coming out of his room.

Danger at Dead Man's Pass

Danger at Dead Man's Pass The Highland Falcon Thief

The Highland Falcon Thief Revenge of the Beetle Queen

Revenge of the Beetle Queen Battle of the Beetles

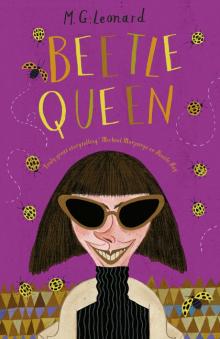

Battle of the Beetles Beetle Queen

Beetle Queen